Look for the Beauty

Think about the last time you were awed by beauty.

Perhaps it was a rising moon, a friend’s smile, a fluffy, toffee coloured puppy, a newborn baby or a stunning landscape. Intentionally placing our attention on the phenomenal wonders we’re surrounded by each day can protect us from negative experiences and reinforce our wellbeing.

A core pathway in the Visible Wellbeing programme at ISWA is attention and awareness. Learning about and practicing these skills is intrinsically linked to wellbeing. According to Professor Lea Waters, creator of ‘Visible Wellbeing, ‘Attention is our ability to focus, whether on inner aspects of self, such as emotions and physical sensations, or on external stimuli. Awareness refers to the ability to pay attention to a stimulus as it occurs. Wellbeing is improved when individuals are aware of, and can consciously direct, their attention’.

From a pragmatic perspective, the ability to be aware and attend to the world around us is essential to survive. There are inherent dangers in this magnificent world, so we protect ourselves by being informed, respectful and mindful of them. It is also commonly understood that without the ability to set our minds to focus and attend to learning, we would remain ignorant and isolated.

Alternatively, though, when we offer up our attention to people, places and experiences or savour them, this can reap phenomenal benefits. Bryant and Veroff (2007) define savouring as ‘…attending, appreciating, and enhancing positive experiences that occur in one’s life.’

What is savouring? Definition, meaning and examples Berkeley

The ISWA Kindy children are masterful at noticing wonders around them every day. They relish moments of close observation such as discovering a budding strawberry or a passionfruit emerging in its infant phase from an exotic flower. They immerse themselves in novel textures such as chocolate coloured mud in their playground creek. They are quick to share their surprise and glee at spotting a kookaburra effortlessly balanced on a branch. They devour celebratory treats, such as birthday cakes, with gusto, oblivious to smears of icing on their faces.

We are all familiar with the cliches entreating us to ‘Stop and smell the roses’ or to ‘Hasten slowly’ and we often remark that ‘Time flies’. As hackneyed and trite as such sayings are, they contain a kernel of truth which is quite profound. This is that our world is sublimely beautiful. We live at a hectic pace in a bustling, frequently overstimulating world.

Deliberately thinking about positive emotions and what generated them is one way of savouring in the present. Buddha says What we think, we become’ so if we are intentional in trying to connect to the present moment, this will spark delight. Alternatively, we can recall moments which have enraptured us. Our imaginations are marvellous tools to help us anticipate what will happen and we can also savour the past. For example, a school camp with Year 4 friends, a relative’s memorable wedding or finally passing our driver’s licence. Mindfully holding onto, and savouring, what feels good, such as the sounds, sensations, sights and smells we experience can be immeasurably enriching.

In the words of Barbara Fredrickson’s “Broaden-and-Build Theory” of positive emotions, such emotions –

“…broaden an individual’s momentary thought-action repertoire: joy sparks the urge to play, interest sparks the urge to explore, contentment sparks the urge to savour and integrate, and love sparks a recurring cycle of each of these urges within safe, close relationships.” (2004)

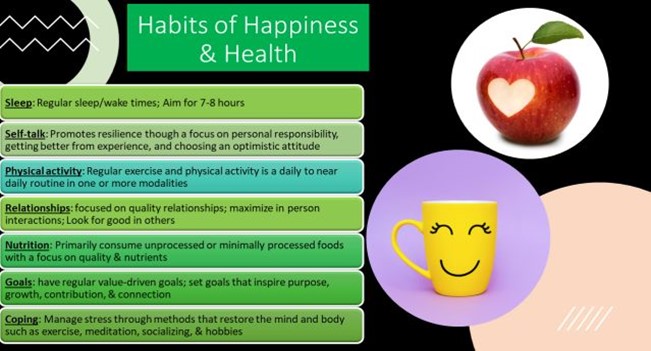

Positive emotions are not just happy feelings, though. They can be the foundation for those fleeting but meaningful moments that make life worth living. They also have other advantages. They can benefit physical and psychological health, promote creative thought and action, support quicker recovery from stress and ‘facilitate more effective coping … buffering us against symptoms of depression’ (Dolphin, Steinhardt + Cance, 2015). At ISWA we encourage students to recognise such emotions and reference them in differentiated ways using specific language such as joy, contentment, hope, gratitude, enthusiasm and affection.

Notions of beauty, of course, vary widely across cultures and eras. Interpretations depend on variables such as geographic region, traditions, religion, age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Perceptions of what is beautiful vary, too, impacting the ways people behave and what is cherished. The earliest philosophers, such as ‘Plato (428–347 BCE), conceived beauty as a form of perfection and eternal truth. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) associated it with harmony, proportion and order’. (Eliseth Leão, 2024) Beauty can also open boxes of tender memories.

So, there are an unlimited range of ways cultivating our attention and awareness can benefit our wellbeing. Engaging in the expressive arts can unite and heal us stimulating our creativity and imaginations. Relishing being outside in nature can amplify good feelings. .Acts of kindness and generosity or a genuine warm smile can be beautiful. Kahlil Gibran said: ‘Beauty is not in the face; beauty is a light in the heart.’

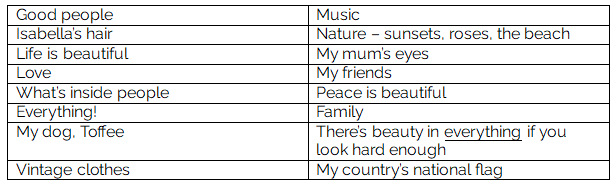

When I asked students, across a range of ages, ‘What is beautiful?’ here are a few of their responses –

When reflecting upon the fundamental meaning of life, Kathryn Mannix, a palliative care consultant (2025) suggested –

‘…wisdom comes when we recognise the pricelessness of this moment. Instead of yearning for the lost past, or leaning into the unguaranteed future, we are most truly alive when we give our full attention to what is here, right now.’

and it is difficult to argue with this perspective.

Christine Rowlands

School Counsellor